Today, BC Mental Health and Substance Use Services staff are helping break down the myths and set the record straight.

"To understand this better, and dispel stigma around mental illness, it's helpful to think of mental illness like a physical illness," says Dr. Tonia Nicholls, a researcher at BC Mental Health and Substance Use Services and a UBC psychiatry professor. Nicholls is the B.C. lead for the National Trajectory Project and specializes in research on people found NCRMD in Canada.

"We see people with cancer or heart disease as victims of a devastating illness. It's no different for individuals with mental health disorders," she continues. "If someone caused a serious car accident as a result of suffering a heart attack or stroke while driving, we wouldn't hold them responsible. We should think of people who perpetrated a crime while suffering from delusions, hallucinations, or symptoms of psychosis the same way. They couldn't help it."

In Canada, someone who commits a crime, but either did not know they were doing something wrong or were not able to control their actions as a result of mental disorder, can mount a defence of NCRMD. It is defined in Section 16 of the Criminal Code of Canada (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46).

"The logic is that someone who acted as a result of mental illness should not be legally or morally responsible in the same way as someone who knew that what they were doing was wrong," says Nicholls.

In Canada, an NCRMD finding is determined through a comprehensive clinical assessment by a psychiatrist and a strict legal test administered by a judge. If the accused individual is found NCRMD, the person generally comes under the jurisdiction of a provincial or territorial review board, who may order an absolute discharge, a conditional discharge, or a custody order, meaning that the person will be treated at a secure hospital.

Nicholls is careful to point out the process is designed to balance the twin goals of protecting the public and protecting the civil liberties and best interests of people with mental disorders.

"A person found NCRMD may be confined at a psychiatric hospital, but that is for the purpose of treatment and public protection—not punishment."

In B.C., a court determination that a person is not criminally responsible, or NCRMD, generally leads to treatment at the Forensic Psychiatric Hospital in Coquitlam, where staff and physicians take steps to ensure the accused, their victims, and the general public stay safe.

"Many individuals who come into the Forensic Psychiatric Hospital for a court-ordered assessment or for treatment under the Mental Health Act show very complex mental health symptoms—approximately 80 per cent of patients at the Forensic Psychiatric Hospital have schizophrenia, and many also live with mood disorders and/or substance use disorders," says Trevor Aarbo, senior director of patient care services at the hospital. "Every day, our clinical teams provide treatment and care, and we see that our patients can get well here and have hope for the future.

"Using the bio-psycho-social care model, we treat people as patients, not criminals, so their symptoms can be managed. Our goal is to provide treatment, and give them skills and rehabilitation so they can re-enter the community safely—while protecting the public."

"Seeing the concepts of recovery and public safety as distinct or even incompatible run counter to decades of research evidence that suggests that punishing people who have come into conflict with the law actually increases recidivism, thus leading to decreased public safety," adds Nicholls.

The following is a case study of a person found NCRMD. His name has been changed to protect his privacy, and his story is used with permission.

Michael is 26 years old. He has been navigating life with a mental illness for 10 years. Until two years ago, he lived at home with his parents and managed to hold down a part-time job close to home. However, everything changed one evening after he assaulted his mother when he was in a psychotic state. The incident sent his mother to hospital with two broken bones. Through a police investigation, Michael went before the courts, and they determined that Michael was NCRMD. At the hospital, after a multidisciplinary assessment, Michael received treatment through medication to manage his symptoms and with psychological services and counselling to help him cope with the shame and trauma of having injured his mother. To help him learn to navigate the challenges of living with a serious mental illness and support a healthy lifestyle, he was also engaged in occupational and recreational therapies at the hospital. Over time, he regained a connection with his family because the family wanted to be involved in his life, and he wanted to regain connection with them.

Receiving a diagnosis of NCRMD is not a "get out of jail free" card, explains Dr. George Wiehahn, the medical director of Forensic Psychiatric Services and the director-in-charge of the Forensic Psychiatric Hospital. "It results in forensic psychiatric care that is, in fact, usually longer in duration than the incarceration time would be if they had been sentenced."

"While someone found NCRMD by a court is not convicted in the traditional sense, it's not the same as being found not guilty—it represents a unique third option," adds Dr. Nicholls. "The person is diverted to the forensic system and comes under the authority of a provincial or territorial Review Board—in our case, the B.C. Review Board, which is accountable to the Supreme Court of B.C."

"This third option exists to best serve both the needs and rights of the individual as well as the needs of the public when there is a risk to public safety," says Wiehahn.

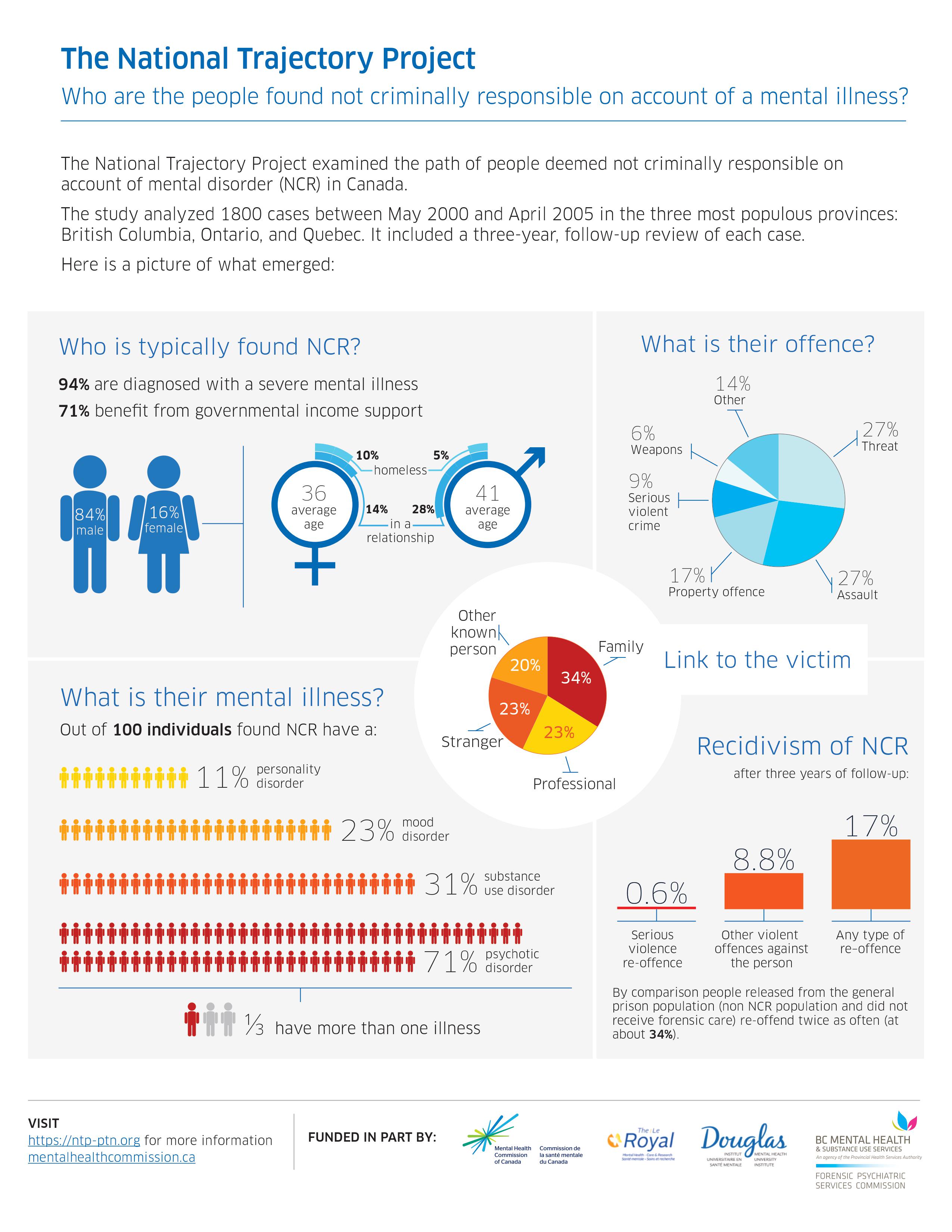

An NCRMD diagnosis does not mean a person is dangerous. In fact, the National Trajectory Project study, published in 2015, studied people found NCRMD in Canada's three most populated provinces— British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec—and found homicides and attempted murder account for fewer than 1 in 10 index offences among people who are found NCRMD. In 35 per cent of cases, the offence involved damage to property and not people.

"Ensuring public safety is always paramount," says Dr. Wiehahn. "However, we are a hospital. That means we treat and rehabilitate patients with the goal of equipping them to re-enter the community when they are ready to do so safely—that is our mandate from the B.C. Review Board."

Rehabilitation and treatment at the Forensic Psychiatric Hospital is customized to each patient's individual history and needs. It may include medication, treatment with a psychiatrist, group therapy, recreational therapy, physical therapy, treatment for a substance use disorder, and more.

Later, when patients are ready and pose a low risk to the public, they practice the life and social skills they learn at the hospital with a carefully considered community outing—first supervised, and later unsupervised if possible.

This is not true. In fact, the National Trajectory Study demonstrated that persons found NCRMD are much less likely to reoffend than people returning to the community from prison—particularly if they suffer from mental health problems. Upon discharge from forensic psychiatric care, people have only a 17 per cent chance of re-offending. In contrast, prior research demonstrates that a person has a 34 per cent chance of re-offending following release from prison.

"There is so much misinformation about our patients," said Dr. Wiehahn. "My hope is that in sharing the facts and talking publicly about what we do, including the fact that our patients do get well, we'll help reduce the stigma surrounding mental illness and substance use. They're people like you and me who became ill, faced some challenges, and ultimately ended up at our facility for help. We're here to help them."